The prompts behind Granola Crunched

We spent three weeks building Granola Crunched, a celebration of your year drawn from your meeting notes. The challenge was as much tonal as it was technical. Crunched had to feel recognizable, observational, funny, and shareable, while avoiding anything creepy, personal, or emotionally speculative. Engineering both sides of that simultaneously, without being able to preview anyone's results, was one of the hardest problems I've ever worked on.

It started with a catchphrase

The earliest foundation came from Luke and Malaika, two interns who'd built the first iteration over the summer. My job, as Granola's resident prompt writer, was to take what they'd started and figure out the prompts we’d ship with - but I only had two weeks to invent and perfect the prompts that powered Crunched.

The catchphrase prompt was the genesis—built originally as a fun thing for an event in SF, boiling down simply to: "tell me what my catchphrase is." It seems simple, but real people don't actually have catchphrases. Is it something that captures your essence? Something you literally say, even if it's not that interesting? Somewhere in between?

To understand it, I had the model show me its working. I wanted to see why it thought a phrase represented me specifically. The process turned out to be unexpectedly introspective and returned a series of devastating psychological insights for me to read in a busy office on a Tuesday afternoon.

That experience clarified two things that initially seemed contradictory:

- Crunched cannot go anywhere near deep psychological interpretation.

- Granola has enough context to do something far richer than surface-level fluff.

The resolution was to focus on purely behavioral insights. Nothing personal, nothing sad, nothing speculative.

The line between behavior and psychology

This distinction became the foundation for everything we built.

Behavioral insights describe what a person does. Psychological insights claim to explain why they do it. Behavior is observable in transcripts: repeated phrases, habits, conversation patterns. "You say 'does that make sense?' a lot" is behavioral because it's literally there in the data. "You seek validation because you're insecure about your expertise" crosses the line—it assigns meaning the person hasn't provided.

The principle is simple: if you can point to it in the text, it's fair game. If you have to guess at why it's happening, the model shouldn't say it.

This is more than a safety measure, it helps to make AI insights feel true rather than invasive. When you tell someone what they do, they recognize themselves. When you tell them what they feel, they get defensive—even if you're right.

The hardest edge cases

Hidden Talent was the category that tested this principle most severely. The very idea implies that a person is unaware of, or underestimates, some part of themselves—which veers close to speculating about confidence or self-perception.

To keep it behavioral, we looked for contrast: moments where the user said one thing about themselves in a meeting, but their behavior consistently demonstrated the opposite. That let us highlight something surprising and flattering without implying anything about their psychology—just evidence-backed observation.

Avoiding buzzfeedification

Early versions of Crunched drifted into "What dessert are you?" territory. If you're closing deals or running public companies, do you really want to know which dog breed you are in meetings? It felt woolly, and it didn't do justice to the available context.

We pivoted to recognizable behavioral categories—things that anyone who works with you would recognize as very you:

- Partner-in-crime

- Achievements

- Skills

- Hidden talent

- Promotion title

- Catchphrase

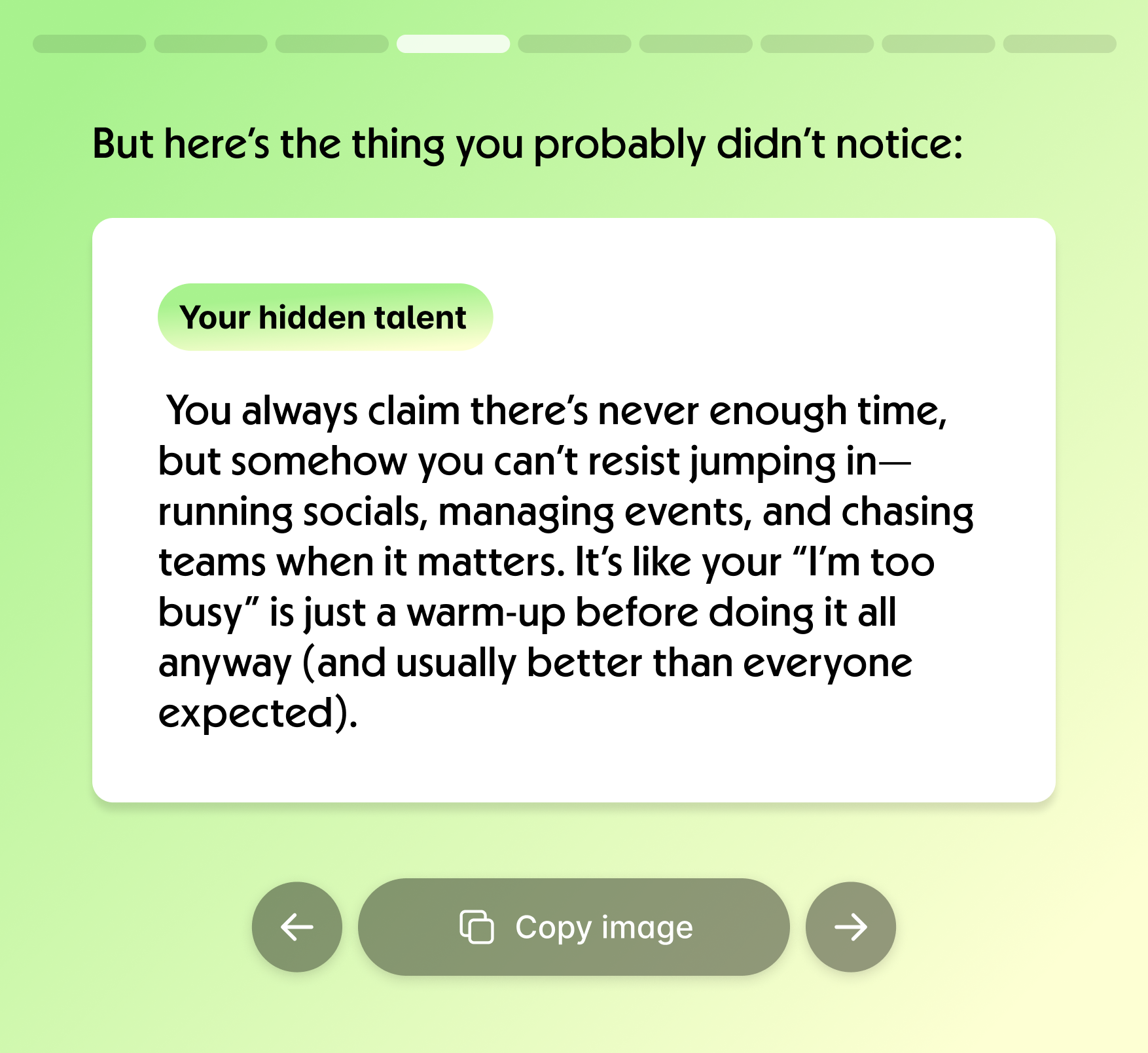

Each category raised its own existential questions. What actually counts as an achievement someone would care about? We ended up writing strict definitions: mix big visible wins with small personal ones; hidden talents must follow behavioral shapes; achievements must include context, role, and a vignette.

What could still go wrong

Even with strict definitions, the failure modes were ever-present in our minds. We kept imagining the worst recipients: someone in HR who'd just delivered layoffs, receiving a cheerful celebration of their year; a job seeker facing repeated rejection, told they were "thriving"; a founder whose company had cratered, served a highlight reel of meetings that led nowhere. Or it could surface something that should have stayed buried—a throwaway gripe about a colleague, a therapy session repackaged as a quip about your relationship.

And beneath all of that: the risk that Crunched just wouldn't land. Not harmful, just forgettable. Cringe. A year of someone's work reduced to observations they didn't recognize or care about.

The problem wasn't that we could list the risks—it was that we couldn't test for them. Every Crunched would be unique. We could run it on ourselves endlessly and still have no idea how it would land for someone whose year looked nothing like ours.

Specificity is proof

Crunched was celebratory by design, which meant the risk of saccharine "glazing" was high. Fortunately, our European-heavy team, acting as guinea pigs, had near-zero tolerance for excessive compliments from a machine.

The solution was specificity. Specificity is what makes a compliment land, because specificity is proof.

"You're a clear communicator" is a claim—it could be flattery, or a guess. "You have a habit of restating what someone just said in fewer words before moving on" is evidence. The first might be true; the second feels like being seen. Specificity earns the compliment.

This connects directly to the behavioral framework: vague praise asserts what someone is; specific praise describes what they do. The moment it drifted into sweeping claims about personality or brilliance, it tipped into cringe - but grounded in a pattern, it felt warm.

Even our prompts were clipped with modifiers. Not 'absurd' but 'slightly absurd.' Not 'a wry twist' but 'a small, wry twist.' The restraint had to be in the instructions, or it wouldn't show up in the output.

Conscious that eight slides of even the driest self-reflection risked navel-gazing, we added colleague celebration/roast slides at the last minute. They ended up being the most shared slides of the whole thing—unsurprisingly.

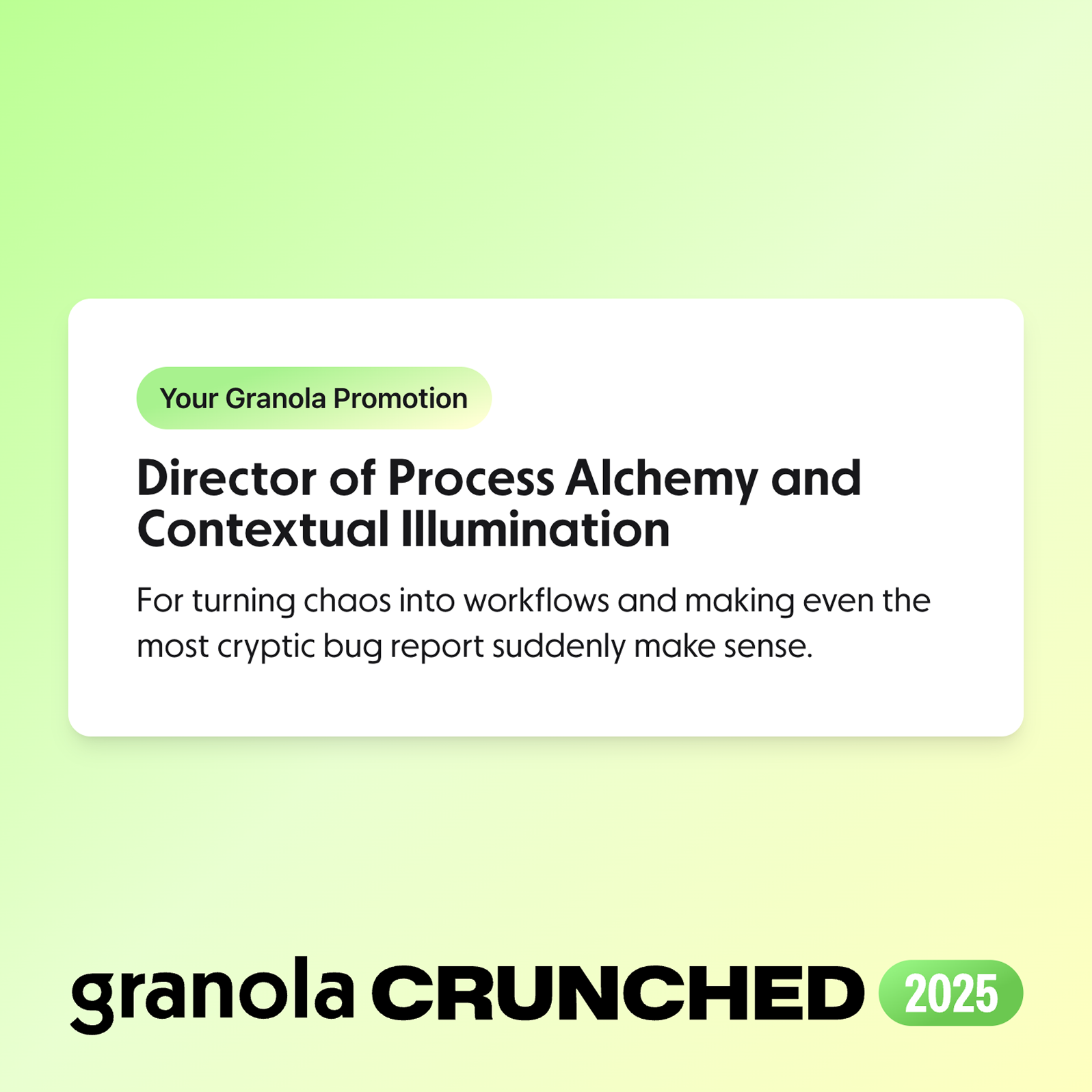

The evolution of a single slide

The promotion slide shows how much iteration each category required. It started as a riff on an existing Granola recipe, "What titles do your team deserve?" Our first version looked like: "Because you're [personality insight], we're promoting you to [title], [funny quip]."

Charming on paper—but incredibly hard to execute. It forced the model to generate three separate insightful, funny ideas from one behavioral observation. In practice, the observation always felt tired by the time you reached the punchline.

I was reluctant to drop the personality insight—it felt genuinely kind and grounded. But once we introduced Hidden Talent to cover that emotional territory, we could simplify the promotion slide to the cleaner "We're promoting you to [title], [quip]." Removing the cognitive load made the outputs consistently funnier. Prompts that try to do too much give the model permission to be mediocre at all of it.

LLMs don't have silliness in their hearts

That's the technical reality. So we engineered humor through structure, constraints, and tone. I ran prompts across my own Granola endlessly, then made fifteen colleagues do the same. The question became a mantra: How does this make you feel? Does this feel better than that? There would be no Crunched without their patience, earnestly explaining to me for the fourth time why a specific catchphrase wasn't funny.

The other challenge was scale. A year of transcripts is too large to query directly unless you want to spend millions. So we built a two-stage approach: a cheap model gathers context, a smart model interprets and writes. This also let us test model pairs specifically for tone—we compared six different combinations to find which was consistently funniest. Some were easily ruled out; others made it to 48 hours before lock.

Launch week

Our sales team ran last-minute interviews with high-risk personas the day before launch. We were ready to delay or cancel Crunched entirely if it performed poorly for them.

They loved it.

We launched early in Europe to watch reactions roll in. By mid-morning, a Figma board we put together to gather feedback was overflowing with screenshots, Slack threads, and cry-laugh emojis. Our carefully prepared "critical feedback to learn from" column stayed relatively quiet.

What went wrong anyway

Grand Vizier-gate. We used "Grand Vizier" as a throwaway example of a bureaucratic title in the prompt. The LLM latched onto it and promoted thousands of people accordingly—cue users on X and LinkedIn explaining Ottoman hierarchy to each other.

The "does that make sense?" epidemic. We'd seen this in testing, but as a team we say it all the time—a tic from working on dense problems—so we assumed it was just our issue. Turns out it was everyone's. It showed up so often that our Slack community spontaneously formed the Make-Sense Club.

The throwaway comment problem. Users sometimes panicked when Crunched referenced something they thought was private—a job search, a difficult project, a confidential deal. Granola hadn't accessed anything it shouldn't have. The user had just mentioned it in passing, in a meeting they'd forgotten was transcribed. A single offhand comment was enough. That's the dissonance: people forget what they've said, but the model doesn't.

What resonated

Looking at what people chose to share publicly, one pattern stood out as being especially reflective of this particular moment in time: users celebrating being told they were more technical than they'd claimed. That gap between self-perception and behavior validated our approach. The model could see something true about users that they couldn't see about themselves—precisely because it stuck to observable behavior rather than psychological interpretation.

What it meant

People found Crunched funny, for the most part. But I've been moved by those who found it something more. One user said it inspired them to get back into a role they'd fallen out of love with. Another had been struggling to find a job; the insights Granola shared from their interviews helped them feel confident they were moving in the right direction - it’s more than we set out to do.

Jo Barrow, Chief of Staff & LLM Whisperer